Treeconomics and the Hedonic Pricing Model

- Carlos Felipe Holguin Isaza

- Mar 2, 2024

- 4 min read

by: Carlos Felipe Holguín

The importance of urban trees

Trees are an essential part of the human environment. Recent studies have found that urban trees offer a diverse array of both economic and quality-of-life benefits that despite not being easily quantifiable, are a common feature of the most livable cities and neighborhoods. Ben Wilson’s book Metropolis[1] exemplifies some of these benefits. Just to borrow some examples, some studies mentioned in the book have shown that the presence of trees can increase by 20% the cost of properties in a given area. Using hedonic pricing, which I will describe in depth below, it’s possible to estimate how much a city values its urban ecology: Between 5.130 and 9.780 million USD for Cape Town, Lanzhou urban forest offers the city an economic service of approximately 14 million USD each year and New York trees generate annual benefits of 120 million USD.

The economic impact of trees is the product of the direct and indirect amenities they create. For some, the scenic beauty that tree canopies create in a neighborhood is enough to make people consider living in them, creating an additional premium for these public amenities. Nevertheless, trees can also provide services that we were not completely aware of until recently. For example, the air filtering and surface cooling properties of trees have been long understood, but it’s only recently that we have been able to quantify them thanks to advances in urban data and remote sensing techniques. For instance, researchers have found that urban trees (depending on the species) capture between 20 to 50 percent of airborne particles, making them essential in highly polluted cities; they also decrease the surface temperature by two to eight degrees Celsius, which in some cities have reduced air conditioning usage by 30%.

¿What is Hedonic Pricing?

Hedonic Pricing is an indirect valuation technique that assumes that the price of a given good (for example housing) is determined by both internal and external factors affecting it. For example, when buying a house we may assume that its price is given by some internal characteristics of the property: its square footage, the number of bathrooms, the materials used in its construction, if it’s a family unit or an apartment in a residential complex, etc. We may also assume that the price is given by some external factors to the property itself, for instance, the neighborhood where the property is located, the local schools, and the number of parks; here is where hedonic pricing comes in handy when trying to estimate the demand (and therefore value) people give to environmental services which cannot be explicitly priced in. In the end, if you have a big enough dataset of prices and characteristics, Hedonic Pricing will tell you the marginal contribution of each of those individual characteristics to the final price of the good being sold, in this example houses.

Hedonic Pricing in Practice

We can model the hedonic price of a property as a regression. Taking our housing example, we can see the price (in meter squre) of a home as a function of a series of internal and external factors or variables. For example, Liisa Tyrväinen (1997)[1] collected sales data on 1006 apartments in the city of Joensuu (Finland), the data points she introduced into her hedonic pricing model are the following:

Housing attribute | Description | Expected sign |

Apartment characteristics (A) | ||

Apartment size | Size of apartment in . | + |

Number of rooms | Number of rooms in each apartment. | + |

Age | Years since the construction of each apartment. | - |

Flat roof | Dummy variable if an apartment has a flat roof. | - |

Renovations | Dummy variable if the apartment has had any renovation in the past. | + |

Façade material brick | Dummy variable if the façade of the apartment is made of brick. | + |

Location (L) | ||

Town center | Distance to the town center measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

School | Distance to the nearest school measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Shops | Distance to the nearest shopping center measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Other public services | Distance to other public services measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Environment (E) | ||

Watercourse | Distance to watercourse measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Wooded recreation area | Distance to nearest wooded recreation area measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Wooded park | Distance to nearest wooded park (Forested area) measured in units of 100 meters. | + |

Low housing density | Percentage of green space. | + |

Own garden | The apartment has a garden | + |

Traffic noise | Presence of traffic noise | - |

Pollution | Presence of pollution | - |

Low “status” of the housing area | The Rantakylä housing district had consistently lower house prices than the rest of the city. Therefore, a dummy variable accounting for this low “status” housing was created. | - |

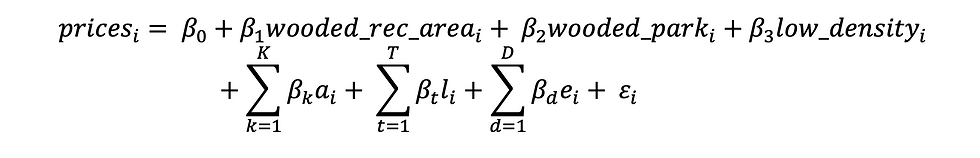

Although not explicitly stated in her paper, the hedonic regression used could have the following structure:

Where a is a vector of apartment characteristics, l is a vector of location characteristics, and e is a vector of environmental characteristics. Her explanatory variables of interest are all related to the distance of apartments to environmental services such as (1) recreational areas (wooded_rec_area), (2) forestry (wooded_park) and (3) the general visual landscape which is proxied as the density of constructions in the area (low_density). In the end, the model renders an approximation of the marginal contribution of each of these factors to the sale value of apartments in Joensuu which is the dependent variable prices. The results show that all the environmental variables considered in the Tyrväinen study, except for the direct distance to the nearest forested park, had a significant positive impact in sale prices of apartments.

Some advantages and shortcomings of the hedonic approach are described in the Handbook on Residential Property Price Indices[1] (OECD, 2013), they can be summarized in the following bulletpoints:

Advantages:

If you have a sufficiently detailed list of property characteristics, then hedonic price regression can account for specific quality changes in individual properties.

A proper stratification of the sample allows the construction of price indices for different types of properties.

The hedonic method is probably one of the most versatile while making use of currently available data.

It’s a highly intuitive method.

Shortcomings:

The method usually requires data on all relevant property characteristics to be reliable.

Different specifications of the model and the inclusion of different variables can render different results on pricing.

Up next

Hedonic Pricing Models are an important tool when considering the price of environmental services, for example, urban trees. In future articles, I will relate more recent articles on this fascinating topic and describe different approaches to environmental services valuation.

Annotations:

[1] Handbook on Residential Property Price Indices. (2013). En OECD eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264197183-en

[1] Tyrväinen, L. (1997). The amenity value of the urban forest: an application of the hedonic pricing method. Landscape And Urban Planning, 37(3-4), 211-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(97)80005-9

[1] Wilson, B. (2020). Metropolis: A History of Humankind’s Greatest Invention. Random House.

Comments